Chances are if you or your children are soccer players then you know at least a few soccer players who have a serious knee injury. The constant running and change-of-direction required to play soccer requires significant lower body strength to perform safely. However, most soccer players pay little attention to lower-body strength. As a result, they are more likely to get injured. If you love soccer, spending some time under the barbell will help protect you from injury, and will probably make you play better.

Soccer is Dangerous

Soccer players are hurt quite often. The injury rate is 62 per 1000 hours. Powerlifting, interestingly, has an injury rate of 0.008 per 1000 hours.1 Knee injuries are common, especially for women. One review found the rate for female soccer players in college sports to be 0.31 ACL injuries per 1000 athlete exposures.2 To give you some perspective, the rate of ACL injury for college football players ranges from 0.124 to 0.173 injuries per 1000 athlete exposures.3 Soccer players are about twice as likely to injure their anterior cruciate ligaments as football players. How do you like those odds?

Stronger is Safer

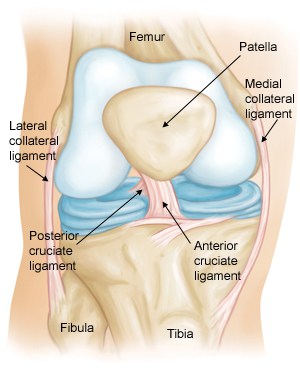

More training of the muscle equals more protection. Think about the structure of the knee. It is a loose, mobile joint protected by ligaments, but also protected by the quadriceps and hamstrings. The quadriceps pulls the tibia by means of the patellar tendon, in which is the kneecap. When the knee is flexed, such as at the bottom of a properly done squat, the patella applies pressure to the joint capsule, acting as a built-in knee wrap. The hamstring muscles pull the tibia to the rear, counteracting the pull of the quadriceps and helping to keep the knee stable. In addition, there is a stretch reflex when a muscle is quickly stretched. The muscle contracts to protect the joint. If I grab your arm and jerk it, you will quickly contract to resist my pull. More muscle, more resistance. Now imagine the situation on the soccer field when you make a quick plant of the foot and turn, or when you collide with another player: there will be very sharp tugs on your leg musculature. Wouldn’t you want to be strong in order to resist damage to your knee?

In fact, studies have shown that greater strength helps prevent injuries.78 Why don’t they just lift weights? It’s actually rather infuriating to read these journal articles and find that no one recommends a simple strength program. If being stronger keeps you from getting injured, why not just get stronger? We know that Olympic weightlifters, who squat deep every day, have very strong knees, very few knee injuries, and healthier and thicker connective tissue in the joint.9 Coaches might fear that their athletes will get slower, there might be lack of time to institute a proper strength training routine, or more likely there might be a lack of understanding of the general adaptation syndrome and how to use it to get stronger. But we here at Chicago Strength & Conditioning can help.

Strength Training is What We Do

If you are a soccer player, do you have an off-season? Then let’s get you on a linear progression, have you squat, bench, press, deadlift, and power clean. In a short time we can make you one of the strongest players on the field. During the season we can adjust as need be. For a novice, you can likely just continue the program, although we might have to adapt the frequency to allow you to perform in games and still recover. Don’t be afraid that muscle will make you slower. It won’t. As Mark Rippetoe says, cars don’t get slower when you put a bigger engine in them. You’ll be stronger, faster, you’ll be able to kick the ball harder, and you’ll be safer from injuries. Let’s get you started.

Book Your Free Consultation

If you’re convinced that the soccer player in your life could benefit from strength training, or you have questions, please contact us today.

References

-

Hamill, B. “Relative Safety of Weightlifting and Weight Training,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 8.1 (1994): 53-57. ↩

-

Dragoo, Jason L., et al. “Incidence and Risk Factors for Injuries to the Anterior Cruciate Ligament in National Collegiate Athletic Association Football.” American Journal of Sports Medicine 40.5 (2012): 990-995. ↩

-

Arendt, Elizabeth A., Julie Agel, and Randall Dick. “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Patterns Among Collegiate Men and Women.” Journal of Athletic Training 34.2 (1999): 86–92. Print. ↩

-

Nebelung, Wolfgang et al. “Thirty-five Years of Follow-up of Anterior Cruciate Ligament—Deficient Knees in High-Level Athletes” Arthroscopy 21.6 (2005): , Issue 6 , 696 – 702. ↩

-

Yoo, Jae ho et al. “A meta-analysis of the effect of neuromuscular training on the prevention of the anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 18 (2010): 824-830. ↩

-

Sugimoto, Dai et al. “Dosage Effects of Neuromuscular Training to Reduce Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes: Meta- and Sub-Group Analyses.” Sports Medicine 44 (2014): 551-562. ↩

-

Khayambashi, Khalil et al. “Hip Muscle Strength Predicts Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Male and Female Athletes: A Prospective Study.” American Journal of Sports Medicine 44 (2016): 355-361. ↩

-

Luedke, Lace E., et al. “Association of Isometric Strength of Hip and Knee Muscles with Injury Risk in High School Cross Country Runners.” The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 10.6 (2015): 868-876. ↩

-

Hartmann, Hagen et al. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine 43 (2013): 993-1008. ↩