Socrates in the Meno apparently thought that virtue (the ability to do the right thing in a situation) was knowledge. If right action is just knowledge, then it seems it could be taught, right? All you would need to do for your friend would be to tell him the benefits of barbell training and macro-tracking, and he would be fine. This doesn’t happen, of course. There are lots of people who know what the right thing to do is, but who just don’t do it. Have you ever informed a smoker that smoking is harmful? How did that go? The issue isn’t knowledge.

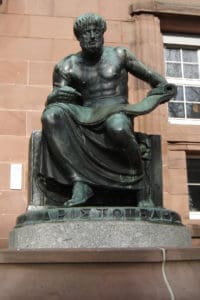

Aristotle describes virtue as being in the state where you do what the wise man or woman would do. In other words, if you were overweight and weak, you would do what Leah Lutz did, take control of your diet, get strong, and be awesome. But it doesn’t usually happen like that. Even for Leah it didn’t happen like that. She eventually hired a coach.

There are four types of people in Aristotle’s writing:

- Virtuous

- Self-controlled

- Incontinent

- Vicious

The virtuous person does what’s right and takes pleasure in it. Aristotle says “the temperate (virtuous) person is the sort to feel no pleasure contrary to reason.”1 You may have a friend who always eats the correct amount and naturally is lean. “How do you do it?” you say, and she says, “I just eat whatever I want.” If you ate whatever you wanted, you’d be a mess, but she is different. She only wants the right amount. She’d feel lousy if she ate incorrectly. She’s virtuous with regard to food, which means her desires are correct.

The self-controlled person is different. He wants to eat the stuffed-crust bacon pizza, but knows that he shouldn’t. More than that, he actually succeeds in eating correctly. It’s just not fun for him. People like him may constantly complain about macros on Instagram, but he’s actually doing well. He’s accomplishing what he has set out to accomplish. He’s training and eating right, but he hates doing it.

The incontinent (or weak-willed) person knows what’s right. She’s read the Book, she’s bought shoes, she’s fully on-board intellectually. Yet, Monday comes along and the thought of three sets of five makes her sad. Suddenly she feels sick, remembers all the work she has to do, and promises herself she’ll get back to lifting Tuesday. Days go by, and before she knows it, she hasn’t trained in a year. She may say to you, “I really need to get back to the gym.” “Today’s a good day,” you reply, but you know she won’t go.

The vicious person likes being out of shape and unhealthy. He’s thoroughly committed to a self-destructive lifestyle. Such people aren’t going to change absent some kind of rock-bottom moment, some self-realization.

Most of us are either self-controlled or incontinent. Here’s where Aristotle can help us. “Virtues, however, we acquire by first exercising them.”2 You become just by acting that way. You become temperate with respect to food and drink by acting the right way. Perhaps you can become good at lifting and eating by lifting and eating well. What I mean by “good” here is psychologically good. You become the sort of person who enjoys the gym by going to the gym. It seems paradoxical that you have to do the activity to acquire the virtue of enjoying the activity, but that’s just the way it is. The first time you tasted bourbon, it probably didn’t taste great. But you accept the word of your bourbon-educated friends, give it another try, and eventually you are able to appreciate the wonders of bourbon. Why would the gym be any different?

The problem is, you’re a mess. You don’t manage to stick to your schedule, and you can’t resist the large double-stuffed bacon pizza. What can you do about it? Aristotle wrote his works for future politicians who would be able to shape the laws to make people virtuous. You don’t have that option. You need to compel yourself. How about this: hire a coach and pay up front. Now that you have sunk money into the project, you will be highly motivated to continue. This is why I don’t give coaching away free to friends and family—if they don’t pay, they won’t continue with the program. They need some skin in the game.

After you’ve paid, show up and act like you like lifting, even if you don’t. The repeated good actions are psychological training. This is why it’s absolutely crucial not to miss training sessions when you are a novice, not so much because you miss the training effect of that session, but because you screw up your transformation into a lifter. Go every day that your program specifies. If you feel tired, go anyway. If you feel sick, go as long as you aren’t contagious. You cannot miss, because you are building the habit. Before you know it, you’ll look forward to going.

In the end, if you are strict with yourself, you can become the sort of person who enjoys lifting heavy things, and who finds pleasure in eating well. At that point the hard part is over, and you are well on your way to strength and health.

Book Your Free Consultation

If you need a coach, or you have questions, please contact us today.